When you leave the Porta Palio Camper Stop Area and begin the short journey towards the Basilica of San Zeno Maggiore, you don’t realize you are about to cross one of the most significant thresholds of Italian medieval art. This church is not just another tourist stop: it is one of the most spectacular examples of Romanesque architecture in all of Italy, a monument that preserves six hundred years of history, legends, and masterpieces that still captivate the eye of those who truly look. Here, San Zeno, the patron saint of Verona who originated from Africa, rests in the crypt, surrounded by stories of miracles and the aura of a figure who converted an entire city to Christianity. And as you ascend the steps towards the entrance, the facade itself—with its chromatic interplay of tufa and brick, and the mysterious rose window known as the “Wheel of Fortune”—already speaks to you of a medieval Verona you will have the privilege of encountering face to face.

From the Camper Van to the Basilica: A Fascinating Route

Having left the Porta Palio Camper Stop Area on Via Gianattilio dalla Bona, the basilica is surprisingly close: about 1.3 kilometers and a fifteen-minute pleasant walk on foot. After passing the automated barrier of the stop area, you will follow Porta Palio, the monumental 16th-century entrance to the city, continuing towards the medieval heart of Verona. The route takes you through the streets of the neighborhood of the same name, an area rich in colorful houses and authentic views, where history still seems to inhabit the walls. As you walk, you will notice how the atmosphere changes: from the noises of modern traffic to quieter, more atmospheric streets. It is not a tourist march, but a gradual approach that prepares the spirit for what you are about to encounter. You can also opt for a bicycle (the cycle path is excellent) if you prefer an even quicker option, reaching the basilica in just 5–7 minutes.

The Basilica of San Zeno: Nine Centuries of Architecture and Mystery

The Basilica of San Zeno is not a church built once and left identical over time: it is the result of a struggle against the elements, of reconstructions and artistic visions that have succeeded one another through the millennia.

The Origins and the Romanesque Reconstruction

The first church arose here around the 6th century, built over the tomb of Bishop Zeno in the early Christian cemetery near the Via Gallica. But its history is tumultuous: destroyed by the Hungarians in the 9th century, rebuilt by order of King Pepin and consecrated in 806, it still suffered barbarian invasions. It was the catastrophic earthquake of 1117 that gave rise to the building you see today. Between 1123 and 1138, Veronese master builders erected a new basilica according to the canons of the Veronese Romanesque style—an art that reflects the Lombard-Emilian influence in Veneto. The work was not completed until 1398, when the architects Giovanni and Nicolò da Ferrara added the Gothic alterations to the apse and ceiling. What emerges is a cohesive building, where the Romanesque style predominates but the Gothic style whispers from the presbyterial throne: a testament to how the Middle Ages transitioned into the Renaissance.

the six 14th-century statues

Virgin with Child Enthroned

The Facade: Geometry and Color

As soon as your gaze falls upon the facade, you are captivated. It features an elegant gabled structure, typical of Romanesque architecture: two triangular pilasters divide the surface into a central body and two lower side wings, creating a balance that speaks of divine proportion. But what truly captures the eye is the chromatism: the alternation of tufa and brick, the pink Verona marble, create hues that change with the daylight, giving the facade an almost mutable quality, as if it breathes with the sun’s rays. The protagonist is the great rose window—the “Wheel of Fortune”—a work by Master Brioloto in the 12th century, decorated with six statues that represent the alternating phases of human fortune: from king to beggar, from beggar to king, a sculptural narrative of change and the transience of the human condition.

The Protiro (Portico) and the Bronze Doors: Portals to the Other World

The entrance is heralded by the protiro (small portico), a stone aedicule supported by columns resting on stylophorous lions in red Verona marble—sculptures that seem to guard the passage between the sacred and the profane. It is here that Master Niccolò signs his work with his vision: a lunette in which San Zeno slays the infernal dragon and offers the municipal standard to the nobles and the people. Around the protiro, 1138 reliefs depict scenes from the Old Testament (the work of Niccolò) and, on the right, the New Testament (Master Guglielmo), among the most significant achievements of medieval Romanesque sculpture.

But the true glory is the bronze portal: 48 square panels constitute an extraordinary work of medieval art—biblical episodes and allegories that seem to move in the light, creating shadows and depth that bronze offers like no other material. It is not mere decoration: it is visual catechesis for the faithful who could not read.

The Interior: Three Levels, Three Worlds

You cross the threshold and immediately feel the gravity of the space. The basilica develops on three levels, and this triple structure is not casual: it represents the descending spiritual journey.

The Parish Church (Chiesa Plebana) is the first level, where light enters through mullioned windows and single-lancet windows, illuminating the three naves supported by cross-shaped columns alternating with simple columns, all with Corinthian capitals. The ceiling is that wooden masterpiece shaped like a ship’s keel that you will also find elsewhere in Verona—a metaphor for the sacred space as the ship of salvation. Frescoes from the 12th–14th centuries are still visible on the walls, some already crumbling with time, others still vivid, works by anonymous masters and by names such as Altichiero da Zevio and Martino da Verona. You can notice how the Germanic monks left graffitied writings with their names on the paintings—an informal memory of those who prayed and meditated in this church.

The Presbytery (or Choir), the second level, is reached by climbing two marble staircases. It is separated from the nave by a balustrade screen where fourteenth-century statues of the German school stand out, depicting Christ and the Apostles—figures that look towards the altar as if in perpetual adoration.

The Crypt, the third level, is the spiritual heart: you access it by descending from the central nave. It is a labyrinth of nine naves supported by 49 columns, with cross vaults creating a masterful subterranean space. Here, the body of San Zeno has rested since 921, visible in a sarcophagus with the face covered by a silver mask. It is a moment of almost overwhelming stillness—you are underground, beneath centuries of stone and prayers, in the presence of a man who walked the streets of Verona two thousand years ago teaching the Gospel.

The Mantegna Triptych: When Painting Becomes Architecture

Ascend to the presbytery again and your gaze is immediately captured by the altarpiece: the Triptych by Andrea Mantegna, dated 1456–1459. It is one of the most revolutionary works of the Italian Renaissance, and understanding why requires you to stand before the painting with intention.

Mantegna, a young Paduan master who would become one of the fathers of the Renaissance, created a “total” work here: it is simultaneously painting, sculpture, and architecture. The painting is highly refined, rich in antiquarian details (Mantegna was obsessed with Roman art), and full of classical references. The chiaroscuro is such that the figures—the Madonna with Child surrounded by saints—seem to step out of the canvas and physically integrate with the three-dimensional marble frame around the painting. But the supreme genius lies in the internal perspective architecture of the painting: the painted columns and spaces extend precisely along the columns of the basilica’s central nave, becoming a true extension of the church itself. Mantegna specifically had a window opened on the right side of the apse so that the light source in the painting corresponds to the actual light entering the basilica. Stand before it for a long minute, and you will understand why Napoleon stole it in 1797: it is one of the works that define what it means to be a Renaissance painter.

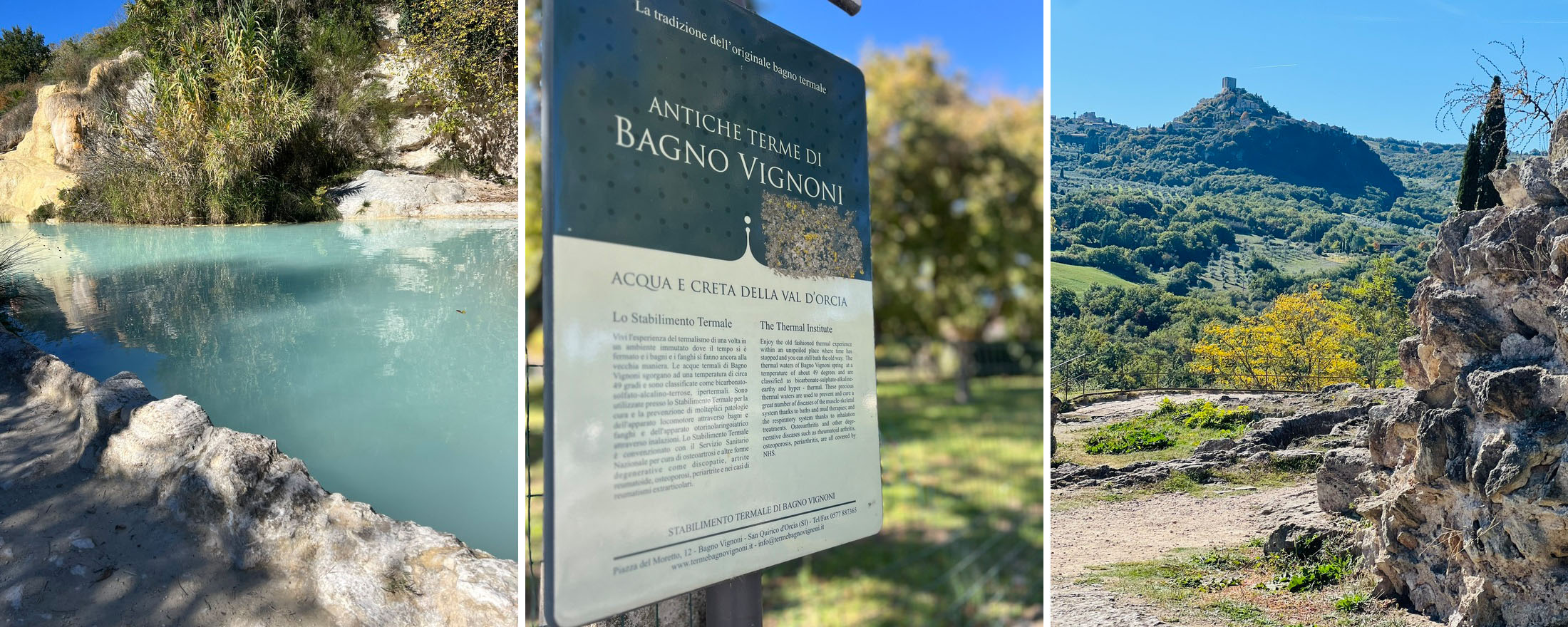

(Note: the altarpiece currently in the presbytery is a copy made by a disciple of Paolo Veronese; the original predella panels are now located in the Louvre in Paris and the museum in Tours.)

Practical Advice for the Visit

Opening Hours

March–October:

- Monday–Friday: 9:00 AM–6:30 PM

- Saturday and Vigil Days: 9:00 AM–6:00 PM

- Sunday and Religious Holidays: 1:00 PM–6:30 PM

November–February:

- Monday–Friday: 10:00 AM–5:00 PM

- Saturday and Vigil Days: 9:30 AM–5:30 PM

- Sunday and Religious Holidays: 1:00 PM–5:30 PM

Important Note: Tourist visits are suspended during religious services. Entry for visits is permitted until 15 minutes before closing.

A cumulative ticket for €18 is available, valid for 90 days, which includes: Basilica of San Zeno, Cathedral Complex, Basilica of Santa Anastasia, and Church of San Fermo. This is very convenient if you are visiting multiple historic churches.

Tickets are purchased at the first church you visit. The audio guide is available in Italian, English, German, French, and Spanish, downloadable via QR code or app.

Recommended Time

1.5–2 hours for a comprehensive visit. If you truly want to absorb the space and the details (frescoes, sculptures, the crypt), dedicate at least 2 hours. If you are rushed, you can visit in 45 minutes, but you will miss a lot.